Leveraging AI Technology for Efficient Infrastructure Management

Introduction and Outline: Why AI for Infrastructure Management

Infrastructure management sits at the intersection of physical assets, human expertise, and time. Every hour of downtime can ripple across supply chains, commuter routes, or service delivery. Costs escalate when maintenance becomes reactive, energy is wasted, and data goes unused. AI offers a practical lift, not by replacing teams, but by giving them better timing, clearer signals, and faster feedback loops. This article explores how automation, data analytics, and predictive maintenance reinforce each other to increase reliability, control costs, and reduce risk without overpromising what technology can do on its own.

First, here is the outline we will follow and expand in depth:

– Framing the opportunity: where AI adds value and where it does not

– Automation: orchestrating repetitive tasks safely and consistently

– Data analytics: turning messy signals into actionable insights

– Predictive maintenance: from scheduled checks to condition‑based decisions

– Integration and roadmap: governance, ROI, change management, and next steps

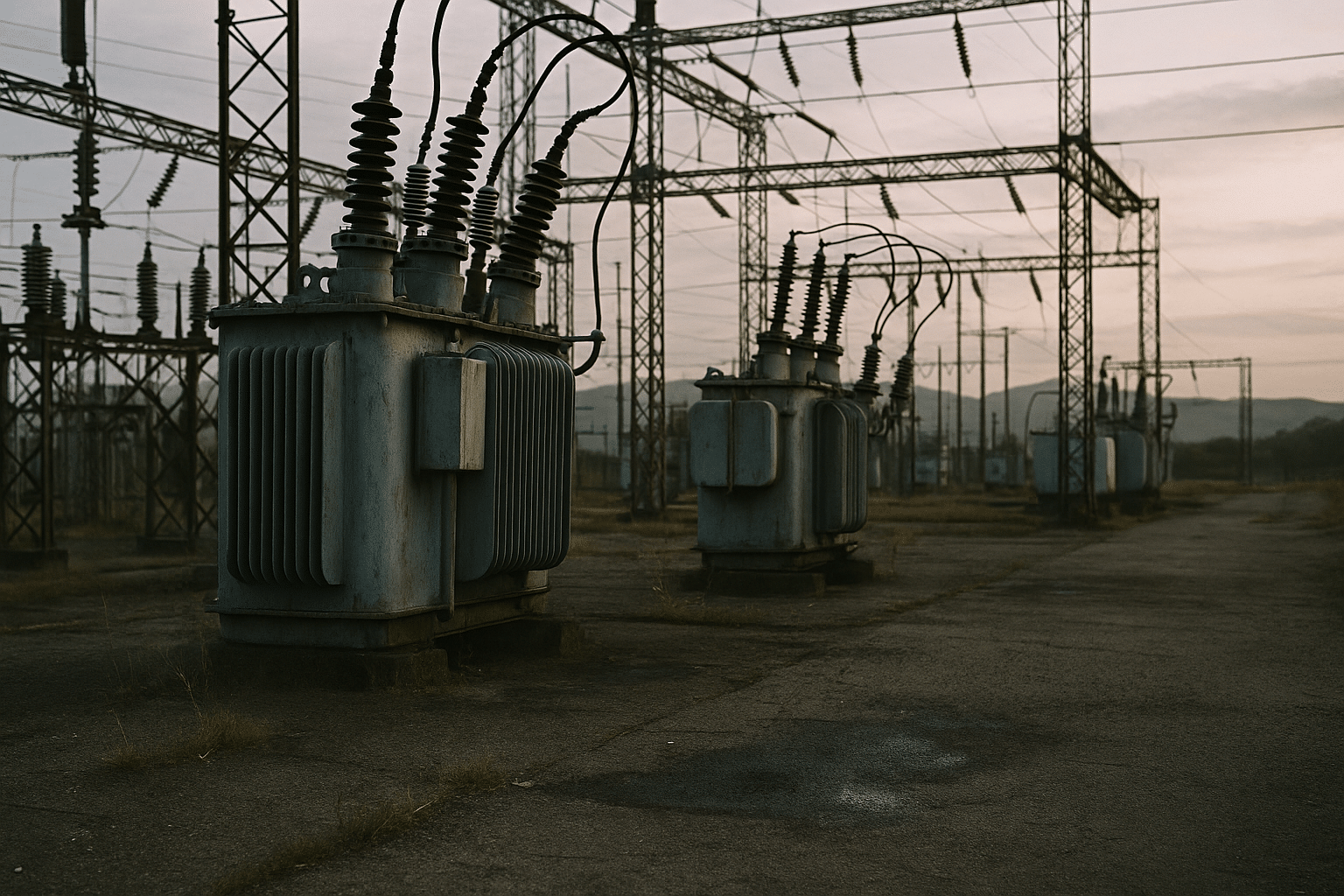

Why now? Sensors are more affordable, connectivity is easier to deploy, and storage has become accessible. Even modest facilities can collect millions of data points daily, yet much of that information still sits idle. Meanwhile, operating budgets face pressure: energy prices vary, spare parts require lead time, and skilled technicians are in high demand. AI helps align scarce resources with the highest‑impact work. For example, anomaly detection can surface a pump imbalance days before it becomes audible; policy‑driven automation can shift non‑critical loads to off‑peak hours; and predictive models can sequence work orders by risk rather than by calendar.

Still, constraints matter. Data quality may be uneven, business processes may be undocumented, and safety protocols must remain paramount. The pragmatic approach is iterative: establish a baseline, choose a narrow pilot with measurable outcomes, and expand only when results are repeatable. Throughout, the focus stays on three metrics that most operators track: uptime, energy intensity, and maintenance productivity. By the end of this article, you will know how these metrics connect to specific AI capabilities, how to avoid common pitfalls, and how to build a roadmap that respects both technical limits and organizational realities.

Automation: From Static Playbooks to Adaptive Operations

Automation in infrastructure management spans simple rule triggers to advanced policy engines that adapt to changing conditions. At its core, automation reduces variance: the same task is executed the same way every time, improving safety and freeing staff for higher‑value work. In practice, the degree of autonomy should match the risk profile of the asset. Low‑risk tasks—such as report generation or routine setpoint adjustments—are ideal for early automation, while high‑risk actions remain supervised with human‑in‑the‑loop controls.

Compare three broad approaches:

– Scripted rules: deterministic if‑then logic for alarms, resets, or notifications. Pros: transparent and easy to audit. Cons: brittle when conditions drift.

– Policy‑based orchestration: higher‑level intents (“maintain temperature range” or “minimize peak load”) translated into actions via optimization. Pros: more robust, supports trade‑offs. Cons: requires modeling and safeguards.

– Learning‑assisted control: models suggest actions based on historical outcomes and real‑time data. Pros: adapts as systems evolve. Cons: needs guardrails, rollback plans, and extensive testing.

Consider a water utility coordinating pumps across pressure zones. Scripted rules can start and stop pumps by thresholds, but they may overreact during demand spikes. Policy‑based orchestration can minimize energy costs by aligning runs with off‑peak tariffs while maintaining pressure constraints. Learning‑assisted control can further reduce cycling by anticipating consumption patterns. Similar patterns apply to building HVAC scheduling, microgrid dispatch, and traffic signaling—each benefits from clear objectives, state awareness, and safe execution logic.

Measurement is essential. Track reductions in manual interventions, variance in key process values, and incident rates. Many operators observe energy savings in the single‑digit to low double‑digit range when moving from static schedules to policy‑based control, with the added benefit of more stable conditions. However, outcomes depend on sensor coverage, actuator reliability, and how well objectives are defined. Automation that chases a single metric (for example, only minimizing energy) can inadvertently increase wear or compromise comfort and service levels if constraints are weak.

Implementation guidance:

– Start with a process inventory: list tasks by frequency, effort, and risk.

– Prioritize steps with high repeatability and clear success criteria.

– Separate observability (sensing and monitoring) from actuation (control), and test each independently.

– Use staged autonomy: recommend actions first, then supervised execution, then limited autonomous control with overrides.

– Keep a playbook for safe fallback modes, including manual reversion and isolation procedures.

Automation succeeds when it is auditable, reversible, and harmonized with operator workflows. The goal is reliable, explainable action—not unchecked autonomy.

Data Analytics: Building a Reliable Decision Engine

Data analytics turns raw signals into decisions. In infrastructure contexts, data arrives from sensors, logs, inspections, and external feeds like weather or tariffs. The challenge is less about volume and more about veracity and context. A practical pipeline includes ingestion, quality checks, feature engineering, modeling, deployment, and monitoring. Each step benefits from explicit definitions: what are the units, sampling rates, tolerances, and business rules?

Types of analytics and where they fit:

– Descriptive: summarize current and historical states (dashboards, baselines).

– Diagnostic: explain why something changed (correlations, root‑cause analysis).

– Predictive: estimate what will happen next (forecasts, anomaly detection, failure risk).

– Prescriptive: recommend actions under constraints (optimization, scheduling).

Data quality must be measurable. Common metrics include completeness (how often data is missing), accuracy (does it match physical limits), timeliness (ingest latency), and consistency (stable units and naming). A simple but effective practice is to define golden datasets—small, vetted time windows used to validate new features or models. Outlier filters should be cautious: aggressively clipping values can erase early warning signals. When sensors drift, analytics can detect gradual baseline shifts rather than flagging a flood of false alarms.

Feature engineering connects physics to data. For rotating equipment, features might include RMS vibration, kurtosis, and spectral peaks; for thermal systems, temperature deltas and gradients; for electrical assets, harmonics and imbalance. External context matters: weather can drive load, and tariff structures can change optimal operating points. Combining these layers often improves prediction stability. Simple models, when fed with well‑crafted features, can rival more complex approaches in accuracy and ease of interpretation.

Model choices should match the question. Linear and generalized models provide transparency for trend tracking. Tree‑based ensembles handle nonlinear interactions and missing values gracefully. Time‑series models can separate seasonality from residual anomalies. Survival analysis estimates time‑to‑event with censored data. For high‑dimensional signals, representation learning can compress inputs before a prediction head, but it requires disciplined validation.

Operationalizing analytics requires governance:

– Version data schemas and models; keep a changelog for reproducibility.

– Establish champion/challenger tests and clear rollback criteria.

– Monitor model drift and alert when performance crosses predefined thresholds.

– Document decisions, including why a recommendation was accepted or rejected.

Finally, align analytics with cost. Not every insight warrants action. A rank‑ordered list of opportunities—by expected impact and effort—helps teams focus. When analytics illuminate a few high‑leverage levers, trust grows and adoption follows.

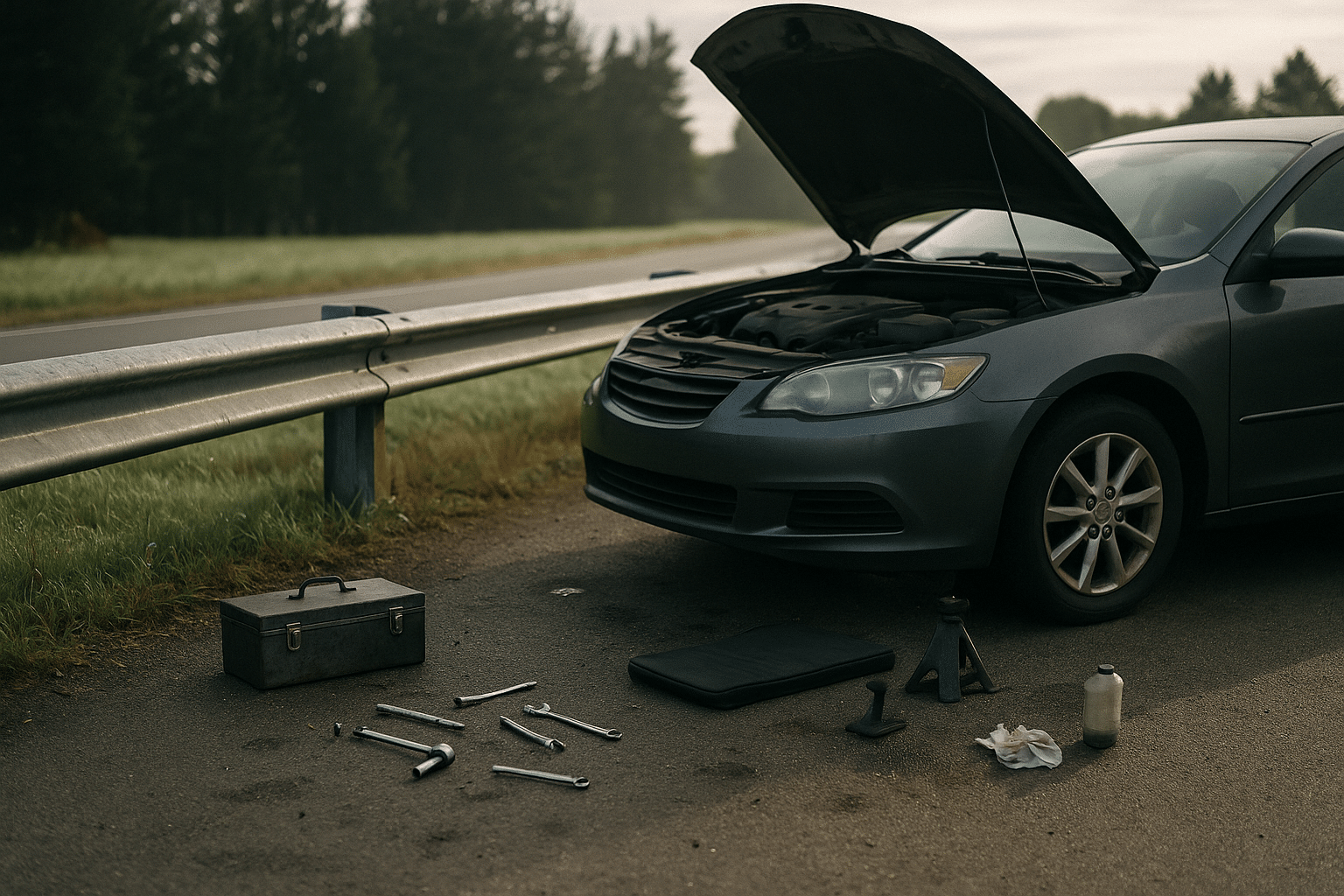

Predictive Maintenance: Anticipating Failures, Extending Asset Life

Predictive maintenance (PdM) shifts maintenance from the calendar to condition and risk. Instead of replacing parts at fixed intervals or waiting for breakdowns, teams act when evidence shows a rising probability of failure. This approach protects uptime and often reduces over‑maintenance. The core ingredients are reliable condition data, a model of degradation, and a decision rule that weighs the cost of false alarms against the cost of missed detections.

Common sensing modalities and their strengths:

– Vibration and acoustic analysis: reveals imbalance, misalignment, and bearing wear in rotating machinery.

– Thermography: highlights hotspots due to friction, insulation breakdown, or load imbalance.

– Electrical signature analysis: detects winding issues, harmonics, and power quality problems.

– Lubricant analysis: surfaces contamination and wear particles.

– Process metrics: pressure, flow, temperature trends that drift from baselines.

Comparing maintenance strategies:

– Reactive: lowest planning load, highest unplanned downtime risk; spare parts and labor calls are unpredictable.

– Preventive (time‑based): predictable scheduling, potential over‑maintenance and unnecessary part replacements.

– Condition‑based: actions triggered by thresholds; balances workload but can be sensitive to noisy signals.

– Predictive (risk‑based): forecasts failure windows and remaining useful life (RUL); enables coordinated outages and just‑in‑time parts.

Evidence from industry surveys suggests that robust PdM programs can reduce unplanned downtime meaningfully, cut maintenance labor spent on low‑value tasks, and extend asset life through gentler operation. Results vary with sensor coverage, model accuracy, and operator response. A practical target for early deployments is to capture a few high‑impact wins—such as preventing a major pump or transformer failure—while establishing trustworthy processes for labeling events, validating alerts, and tuning thresholds.

Modeling techniques include hazard models for time‑to‑failure, regression for RUL estimation, and classification for near‑term failure risk. Ensembles that combine physics‑informed features with data‑driven patterns often generalize better than either alone. When labeled failures are scarce, semi‑supervised anomaly detection can flag deviations from healthy baselines. Key pitfalls to anticipate:

– Label scarcity and bias: few failures mean limited examples; augment with expert annotations and simulated faults where appropriate.

– Non‑stationarity: operating conditions, loads, or maintenance practices change; use time‑aware validation and retraining schedules.

– Sensor placement: poor mounting or interference degrades signal quality; invest in installation and commissioning checks.

– Actionability: alerts must map to clear tasks; provide diagnostic context, not just scores.

Success hinges on closing the loop. When an alert is issued, capture what was inspected, what was found, and what was done. This feedback strengthens models and helps prioritize the signals that consistently lead to meaningful interventions. Over time, PdM becomes less about prediction scores and more about dependable decisions.

Integration, Governance, and a Practical Roadmap (Conclusion)

Turning AI from a pilot into everyday practice requires integration across people, processes, and technology. The roadmap begins with business objectives—higher uptime, steadier quality, lower energy intensity—and works backward to the minimal data and control needed. Stakeholders should include operations, maintenance, safety, finance, and IT/OT security. Clear ownership prevents drift: who approves model changes, who signs off on automated actions, and who audits outcomes?

A phased approach can reduce risk:

– Phase 1: Visibility. Instrument critical assets, standardize naming, and publish live baselines and alerts without automation.

– Phase 2: Assistive analytics. Prioritize work orders by risk; schedule inspections when anomalies persist; track precision and recall of alerts.

– Phase 3: Supervised automation. Execute low‑risk control actions with operator approval; measure impact on stability and energy.

– Phase 4: Limited autonomy. Allow bounded, reversible actions within strict guardrails; maintain overrides and fail‑safe modes.

Governance is not red tape; it is how reliability is maintained. Establish change control for models and data schemas. Log every automated action with context and outcome. Conduct periodic reviews focused on safety incidents, unexpected interactions, and lessons learned. Security cannot be an afterthought: segment networks, restrict privileges, and monitor for anomalies across both IT and operational networks. Training matters too—equip teams to interpret analytics, understand model limits, and intervene confidently.

For asset owners and public service operators, a reasonable target is to deliver value within one budget cycle while laying groundwork for scale. That means scoping pilots around measurable outcomes—avoided outages, verified energy savings, or reduced inspection hours—then capturing before/after baselines. Document playbooks so success is repeatable, not personality‑driven. As maturity grows, broaden coverage methodically rather than chasing novelty.

In closing, treat automation, analytics, and predictive maintenance as a single system that senses, decides, and acts with accountability. Pick narrow, high‑impact use cases, invest in data quality and guardrails, and measure results against stakeholder goals. With this discipline, organizations can modernize infrastructure operations, protect service continuity, and fund the next wave of improvement through verified gains.